Story by Micheal Stein | Photography by Jason Moore | Hawai‘i Superferry

The Hawai‘i Superferry logo of manta rays gliding through the sea perfectly captures the decades-long desire of Hawai‘i residents for swift, efficient ocean transportation between O‘ahu and the neighbor islands. And judging from the website, the Superferry looks like it will be sleek, comfortable and a lot of fun.

The Hawai‘i Superferry logo of manta rays gliding through the sea perfectly captures the decades-long desire of Hawai‘i residents for swift, efficient ocean transportation between O‘ahu and the neighbor islands. And judging from the website, the Superferry looks like it will be sleek, comfortable and a lot of fun.

There will be dining areas, a retail store, the Hahalua (Manta Ray) Lounge, and a playroom for the keiki (children), not to mention amusements teenagers and adults will appreciate, like newly released movies on flat-screen TVs and videogames. There will also be the chance to simply gaze at the stunning perspective of a Hawaiian harbor looming ever closer across the open ocean. When you disembark, there’ll be no lineup to rent cars, because your own vehicle will have taken the voyage with you.

Governor Linda Lingle and Senator Dan Inouye have long been enthusiastic supporters of the project. Maui Land & Pineapple Company, Inc., invested a million dollars in the Superferry because of what Maui Chamber of Commerce President Pamela Tumpap calls its “expanded delivery options for Maui businesses,” such as refrigerator-truck power outlets for fresh-produce transport. And a poll by Pacific Business News found that interviewees support the Hawai‘i Superferry by majorities of over 70 percent.

But that polling and publicity point to the controversy that has shadowed the project from the start. Opponents by the thousands have branded the Superferry a threat to Maui and Kaua‘i’s environment and a shaky business enterprise pushed by O‘ahu over the strong objections of the neighbor island county councils. In fact, after five years of writing about topics ranging from “smart growth” to naval sonar testing’s impact on whales, I’ve never found a subject that people are less willing to comment on or have angrier opinions about. Ironically, a transportation project that may bring the Hawaiian Islands closer together has become an issue that is driving them farther apart.

***

The need for a ferry service has long been apparent, especially after the events of 9/11 shut down all island air travel for almost a week. Superferry’s executive team—Chairman Timothy Dick; John Garibaldi, former chief financial officer of Hawaiian Airlines; and Terry White, former vice-president of American Hawaiian Cruises—saw an excellent business opportunity when examining the Hawai‘i market in 2001. In January of 2004, Hawai‘i Superferry announced that the Australian-owned, Alabama-based company Austal USA had agreed to build two “super-catamaran” vessels for O‘ahu-to-neighbor-island ferry service.

Controversy began to swirl around the project once the State allocated $40 million to construct harbor upgrades at Nawiliwili and Kahului, such as ramps and docking barges to allow cars to transit from the Superferry to the piers below. Such infrastructural changes foreshadowed worsening congestion on docks already becoming more crowded. Canoe clubs feared they’d be driven out of Kahului Harbor waters by the new company’s need for docking facilities.

Meanwhile Spirit of Ontario, Austal’s first SWATH (Small Waterplane Area Twin Hulls) ferry, was taken on a tour of the islands to show off its design and performance. The double-hulled ship, 349 feet long and 80 feet wide, could carry approximately 900 passengers and 200 of their vehicles in an area the size of a three-deck football field. The SWATH design, with its “wave-piercing” hulls, could keep the Superferry comfortable even at its lowest velocity of 3 knots, and the vessel could reach a cruising speed of approximately 35 knots, or about 39 mph.

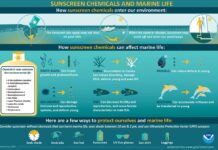

But that raised new fears: a ship moving that fast in Maui waters might be a threat to migrating and calving humpback whales, especially during night voyages. An even graver environmental danger, according to officials at the Maui Invasive Species Committee and the Sierra Club, could be visitors’ cars, camper vans and trucks inadvertently transporting invasive pests all over the islands, such as coqui frog eggs and miconia seeds. The final threat could be those visitors themselves. Mauians familiar with traffic snarls around the Kahului Harbor area imagined what would happen when over a hundred cars were driven on and off the ferry daily.

It didn’t help that Superferry was perceived as a speculative business venture backed by Mainland money and the state capital over the interests of Maui and Kaua‘i. Superferry C.E.O. Garibaldi has stated that the facilities built through the $40 million state loan were not specifically earmarked for Superferry, and that Superferry pays user fees and a general excise tax. Nonetheless Rob Parsons, environmental coordinator for former Maui Mayor Alan Arakawa, labeled Superferry as an “O‘ahucentric” exercise in “corporate welfare.” Project detractors like retired Maui Community College economics professor Dick Mayer pointed to a trail of Superferry political contributions, among them $1,000 to the head of the House Transportation Committee, Joe Souki, and $26,000 to the Lingle-Aiona campaign.

Opposition to Superferry coalesced around the demand that the state legislature require a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to assess the project’s potential environmental and traffic threats. That demand was backed by near-unanimous votes of the Maui, Kaua‘i, and Big Island County Councils—but denied by then-Deputy Director of the Department of Transportation Barry Fukunaga, who stated that the Superferry was no different than any other cruise ship or airplane and did not require a full EIS. A renewed crescendo of opposition over three years mounted to an attempt in early 2007 to pass bills in the Hawai‘i House and State Senate, HB702 and SB1269, that would stop the project until an EIS could be completed. Those measures died when Representative Souki refused to schedule a hearing, once again stating it would be unfair to single out the Superferry.

Responding to objections by environmentalists, Garibaldi has stressed that the Superferry has worked out a “whale avoidance plan” that includes lookouts on the bridge—“double the number of eyes out there”—slower speeds (25 to 13 knots), altered routes north of sanctuary waters during whale season, and plans for night-vision technology and “forward-looking sonar.” The vessel will have concealed propellers and nontoxic slippery paint on its bottom so it won’t damage or transport any marine organisms. As for land-based pests, Superferry’s staff will conduct vehicle inspections on every trip—including more thorough car and truck-body inspections at random—and won’t allow dirty or mud-caked vehicles onboard. “We’ll hire added personnel to manage cars coming into our terminal and screen vehicles,” Garibaldi and Terry O’Halloran, Superferry’s director of business development, told me, with searches of approximately 120 vehicles transpiring over a two-and-a-half hour period before they are allowed to embark.

That hasn’t satisfied Superferry’s opponents. The battle over the EIS isn’t over. Two lawsuits, one of which names the Maui County Council as a party, are pending before the Maui Circuit Court and state Supreme Court. The goal now is not to stop the Superferry but reverse what many feel is a negative precedent, by which a large company has sidestepped the State’s environmental review process. In the words of Lucienne De Naie, interim president of Maui Tomorrow, “the environmental laws can’t be tampered with if these laws are to have any integrity.”

Many environmentalists would agree with Naomi McIntosh, manager of the Hawaiian Island Humpback Whale National Sanctuary, who stated, “The company’s proposal of voluntary mitigation measures is not the best situation we’d like to have. For example, the proposed ‘forward-looking sonar’ is not ready for prime time”—as in still being researched for commercial use. McIntosh told me of a published paper by David Laist, a policy and program analyst for the Marine Mammal Commission, that suggests a vessel has to drive as slowly as 13 knots (not 13 to 25 at the captain’s discretion) to reduce the probability of collisions with whales in migration waters like Maui’s. “We need to sit down with Superferry . . . and work closely with them to minimize the potential risk.” The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has invited the Superferry to apply for an “incidental-take permit,” identifying Superferry as a possible threat to whales and monk seals; Superferry would therefore cooperate with mitigation measures recommended by NOAA. According to McIntosh, the company hasn’t responded to this offer.

***

Ultimately it will be the smoothness or choppiness of the economic waters that will determine Superferry’s fate. Now that an interisland airfare war has lowered some tickets to $19 one way, both O’Halloran and Garibaldi concede they don’t expect to attract the day air traveler—but given the soaring cost of fuel and Superferry’s more efficient energy usage, Garibaldi believes the boat will be more affordable in the long run.

Warren Watanabe, president of the Maui County Farm Bureau and a member of the Maui advisory board for Superferry, told me, “Farmers are open to transportation alternatives to O‘ahu, where most of the local markets are. Young Brothers [freighters] are proposing an increase of their rates that could be cost-prohibitive, and for agriculture on Maui to survive, we need to be able to export.” The Superferry could be very useful for smaller shipments to farmers’ markets, although, as William Jacintho, who both grows bedding plants and raises cattle at his Beef and Blooms, remarked, “Can we make the farmers’ market in O‘ahu on Superferry and have time to come back? Otherwise I have to pay for labor, parking and putting a person up at a hotel. Also, by the time I get to O‘ahu, I might miss half the market day.” Watanabe concedes, “All the details haven’t been worked out, but we’re all trying to find the best way to use the system.”

School athletic directors I spoke to also had a questioning but hopeful attitude. Scott Soldwisch, from Maui High School, told me, “If we could send groups like the girls’ basketball team with a van, as opposed to renting vans over there, it would be a big help.” His view was seconded by Kahai Shishido at Baldwin High, who’d like to use the Superferry for preseason tournaments in O‘ahu. But as Soldwisch also pointed out,

“Having looked at a couple of cost comparisons, I’m not sure it offers a lower-cost alternative, especially for smaller teams. . . . we hear conflicting stories.” Both directors told me they’re looking forward to meeting with Superferry officials to get more answers.

Garibaldi exudes confidence that all such issues will be resolved, and that “the opportunities are unlimited.” And for all the controversy, for all the as-yet unanswerable questions about the Superferry’s potential economic, environmental and social impact, if you check out the palaver on website chat groups like Tiki Talk, many visitors and residents want to give the boat the benefit of the doubt: the couple anticipating a leisurely, beautiful voyage to Kaua‘i; the surfer who wants to bring his board to Pipeline; or the Maui teenager who looks forward to using Craigslist to buy a car in Honolulu. It’s such choices by island residents and visitors, multiplied by the thousands, that will determine whether the Superferry soars like its emblematic manta rays through the currents of interisland travel.

Coming to a Harbor Near You

As of press time, the first Hawai‘i Superferry, christened Alakai (Ocean Path) is undergoing its final Coast Guard testing before heading for Hawai‘i, where it will begin daily service between Honolulu, Maui’s Kahului and Kaua‘i’s Nawiliwili Harbors in late summer. Starting in 2009, a second ferry will make four-hour trips between O‘ahu and the Big Island and additional trips between O‘ahu and Maui. The company plans to announce when it will begin taking reservations for the Alakai, with advance tickets at www.hawaiisuperferry. com.

More details: The Superferry will depart Honolulu at 6:30 a.m. daily and reach Maui at 9:30 a.m.; and leave Maui at 11 a.m. and arrive in Honolulu at 2 p.m. Kaua‘i trips will leave from Honolulu at 3 p.m. and arrive in Nawiliwili at 6 p.m., returning for Honolulu at 7 p.m. and arriving at 10 p.m.

Ferry terminal gates will be open two-and-a-half hours before departure, and will close a half-hour before, to allow time for security and agricultural inspections of passengers and vehicles. Passengers should have a photo ID, and drivers need to have, along with their license and registration, a certificate of inspection for any plants brought on board. If a driver is not the registered owner, he or she must have a notarized letter authorizing that person to drive the vehicle. Forms will be provided with a Superferry reservation; a driver need only obtain this letter once, and there is a plan to streamline this process for rental cars.

Advance-purchase prices on the Web for Maui and Kaua‘i voyages will be $47 at off-peak times (Tuesday through Thursday) and $57 during peak times (Friday through Monday). Regular passenger fare will be $52 and $62. Prices for children 2 to 12 years of age and seniors over 62 will be $41 and $51, and for infants under 2, $17. On the covered vehicle deck, cars and SUVs will travel for $59 and $69. For rates for motorcycles, pickups and freight trucks, and for charges for transporting canoes and bicycles, check the website at www.hawaiisuperferry.com.

You can also get tickets by calling 1-877-HI-FERRY or at the Superferry terminal on the makai (oceanside) corner of Pu‘unene and Ka‘ahumanu Avenues.

Ferry operations were suspended in March, 2009 after the Hawaii Supreme Court ruled that a state law allowing the Superferry to operate without a second complete environmental impact statement was unconstitutional. The company went bankrupt as a result of these actions preventing service in Hawaii.

SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hawaii_Superferry

Wow, this service sounds wonderful – what happened to it?