Story by Rita Goldman | Photography by Lisa Kristine

Elizabeth Lindsey is a child of the Islands; her Hawaiian blood mingles with that of English seafarers and Chinese merchants. The Hawaiian elders who raised her “remem-bered the names of the wind and rain,” and instilled in her a reverence for the wisdom of stories. “They told me that I would travel far to keep the voices of the ancestors alive,” she says, “and that it would take the wisdom of these elders to return the world to balance.” Half a century later, Lindsey travels the world, collecting ancient knowledge to create a map of the human story that may someday help all of us navigate the future.

Elizabeth Lindsey is a child of the Islands; her Hawaiian blood mingles with that of English seafarers and Chinese merchants. The Hawaiian elders who raised her “remem-bered the names of the wind and rain,” and instilled in her a reverence for the wisdom of stories. “They told me that I would travel far to keep the voices of the ancestors alive,” she says, “and that it would take the wisdom of these elders to return the world to balance.” Half a century later, Lindsey travels the world, collecting ancient knowledge to create a map of the human story that may someday help all of us navigate the future.

MNKO: How would you describe your Map of the Human Story?

Lindsey: My field of study is cultural intelligence—the knowledge that has existed throughout the world and across millennia. We are alive at an age when there are still elders whose wisdom is available. The goal is to marry that ancient wisdom to twenty-first-century technology; to create a cultural repository that people will continue to contribute to, so it is always dynamic and evolving.

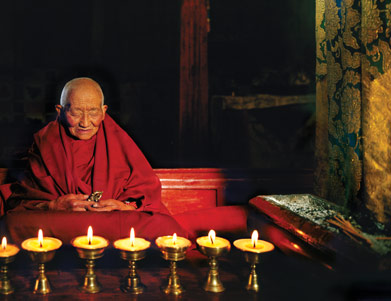

We’re looking to imbed media of all kinds—film, photographs, audio, text, maps and animation—into this repository; it will make for a much richer, much more inclusive way for the world to tell its story. I’ve been working with photographer Lisa Kristine. She is utterly gifted and a joy to work with. We’re traveling around the world over the next twelve months, photographing, filming and recording. I hope to have enough documentation to launch the Map of the Human Story, as well as an exhibit and book.

How does this relate to your studies in ethno-navigation and your time with master wayfinder Mau Piailug?

I spent ten years with Mau and will always be grateful that my bumbling route led me to a teacher of such brilliance. I’m not a navigator. I’m in awe of them, the way they can synthesize seemingly unrelated data—the movements of waves, stars, and seabirds—to gain their bearings. I went to Google and said, “If they can do this on the ocean, you can do this with technology.”

We have never before been in a position to be as connected as we are now, to be able to report in real time and forecast the human condition. That’s part of why I am working with Google. The only way for us to dissolve the illusory boundaries that separate us is to share our stories, to see that people we perceive as foreign, as enemies, as challenges to our society . . . are human beings whose heart beats like our own. The more intimate we become with one another, the more the notions of separation and war seem insane.

Can you give an example of the kinds of stories you’re collecting? Are they histories? Parables?

Can you give an example of the kinds of stories you’re collecting? Are they histories? Parables?

There’s a story that the spider will leave its web before a bad storm. If you wish to be forewarned, you look to see what the spider has done. A woman in Kohala, Aunt Marie Solomon, told me that. She also told me that a certain tree will drop its leaves when a certain school of fish is ripe for fishing. These small stories are extremely valuable. They teach us about natural cycles; they speak to an intimate relationship with the natural world.

Throughout time, cultures have had brilliant technology that Western society has marginalized or dismissed as “primitive.” These cultures are highly sophisticated. They have much to teach us in the West, we who don’t know where our food comes from, who couldn’t glean resources for ourselves if there were a social breakdown.

I was recently in Sardinia, talking with elders, all of them over 100 years old, all of them independent, vibrant, clear-thinking. Not one indication of dementia. These were people who had experienced great loss in their lives—war, the death of children—but they were still very much integrated into their communities. When I asked what keeps them vibrant and dynamic, four things became clear. First, what they eat is close to the source; it hasn’t been compromised. Most were raised growing their own food. Second, they have been active throughout their lives. Third was the ability to use meditation or some other means of decompressing the stress in their lives. Last, and perhaps most important, they all said they had a sense of belonging, of family and community, that gave their lives purpose.

In collecting elder wisdom, how important has it been that you yourself are an indigenous person? I’ve noticed a kind of cultural fatigue among some Hawaiians; they resent being expected to share their knowledge with outsiders who often misinterpret or profit from the information. How does one respectfully approach and use such knowledge?

In Hawai‘i, there’s a real tension between Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians because of acculturation and colonization. A number of elders I was raised with were photographed and filmed and documented, and the people who extracted this information would never be seen again. It benefited the outsiders, not the people who held the wisdom. We have to make sure there is reciprocity and proper acknowledgement given; that benefits are shared.

I sit on a United Nations’ board for environmental refugees. My focus is islands; Mau asked me to help his island before he passed away.

In Puluwat, a small island in Micronesia, people weren’t aware of the climate crisis, but they knew that the sea is rising, making the water on the island brackish, which destroys the roots of their staple crops. There have been many conversations around relocating the people, but the elders won’t leave. That’s where the bones of their ancestors are; it’s their umbilicus.

At the UN, we’re working on alternatives to relocation, on desalinization systems that operate on solar, and on raising awareness. People think it’s not important; these are faraway islands with small populations. But islands are the canary in the coalmine. Manhattan is an island, too. What’s happening in Micronesia will happen elsewhere.

Do you think we Westerners will listen?

Do you think we Westerners will listen?

Last February, I opened the Global Leadership Summit for the YPO/WPO—Young Presidents Organization/World Presidents Organization—17,000 members. If you added all their corporate assets, they represent the fourth wealthiest country in the world. I was curious why they would have an anthropologist open the summit. They said, “We understand that many of the choices we’ve made are not sustainable. What we’ve been doing isn’t working.” I was talking about wayfinding as a metaphor for one’s life and one’s organization. These were men and women at the highest executive level, needing to find the way for their organizations. Those positions are among the loneliest in the world. So we talk about finding our center again and navigating from a place of deep knowing.

It’s not enough to look at our fiscal bottom line. We have to reframe what success looks like. “Wealth” comes from wellah, which means “well-being.” We have reduced it to money; I ask people to go back to the original definition.

Most of us don’t want to give up our comfortable Western lifestyle.

We can live in modernity, but use the ancient and indigenous knowledge as reference. Being both a Native Hawaiian, and a trained scientist, I straddle these worlds and see how similar they are.

That touches on a question I had earlier: how indigenous cultures can advance without losing their authenticity.

“Preserving culture” is a static thought. No culture can thrive by being static. The Hawaiian elders who raised me would look for what was available and build on it.

Here in Hawai‘i, the interest in indigenous wisdom is very alive, but elsewhere, younger generations are not interested. From Bhutan to the Pacific, they are seduced by the Western world.

How do you make elder wisdom compelling to the next generation?

Speak to young people in a language they’re using. Give them platforms and bandwidths to tell the stories that are meaningful to them. The people I’ve been working with the last few years, whom I admire, have great respect for the potential of integrating these technologies.

In Western society, we tend to compartmentalize knowledge. A native mind will look for the holistic possibility. If we tell children, “You’re texting too much; you’re on the phone too much”—if we condemn these technologies, they’re left with having to choose between their culture and a technology that’s popular with their peers. We create a schism, separating them from something that could be a wonderful ally.

I was in southern India last year, creating curricula to expand familial engagement. You sit in schoolrooms and say, “Tell me the stories of your grandparents. Use anything you want: a notepad and pencil, a recording device, or video camera—whatever.” Wondrous things are born of this intergenerational exchange.

The elders say that storytellers are the wisdom people. How we see the world is how we tell our story. I want my life to be devoted to the way people see their lives as rich and valuable, and an integral part of humanity’s story. If one story is missing, the tapestry is incomplete.