Crowded, crumbling docks. Inadequate restroom and pump-out facilities. Cruise-ship chaos. Welcome to Hawai‘i’s small-boat harbors. Decades of disregard led the State’s auditor to report, in 2001, “The boating program’s mismanagement and neglect have deteriorated facilities to the point where their continued use threatens public safety.” Little has changed since; in a state dependent upon ocean activities, even basic boating needs are not being met.

Crowded, crumbling docks. Inadequate restroom and pump-out facilities. Cruise-ship chaos. Welcome to Hawai‘i’s small-boat harbors. Decades of disregard led the State’s auditor to report, in 2001, “The boating program’s mismanagement and neglect have deteriorated facilities to the point where their continued use threatens public safety.” Little has changed since; in a state dependent upon ocean activities, even basic boating needs are not being met.

Fortunately, a rising tide of public awareness and big new federal funds could propel recreational boating in Maui County onto a new course for the future. State Boating Administrator Richard Rice is like a man with his finger in the dike. He took the helm of the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resource’s Division of Boating and Recreation (DLNR-DOBOR) nearly two years ago. Considering the job’s challenges, one has to wonder why. “I was well aware of the problems,” Rice says. “But it’s not only kids who say, ‘I just want to make a difference.’ I think boating has a very good story to tell.” He adds with a laugh, “And I couldn’t make it any worse.”

Hawai‘i’s boating program under the jurisdiction of DLNR-DOBOR is technically self-sustaining. A handful of harbors across the state generate revenue, which is pooled and redistributed to help smaller facilities. Maui County claims two of six lucrative harbors: Lahaina and Ma‘alaea. Other facilities include Hana and Mala wharves; Kahului, Ke‘anae, Kihei, and Maliko boat ramps; Ka‘anapali and Lahaina anchorages; and Manele, Hale o Lono, and Kaunakakai harbors. All are in dire need of attention.

Luckily, boating just got a boost from Washington. Since Senators Dan Inouye of Hawai‘i and Ted Stevens of Alaska represent states without interstate highways, they persuaded Congress to award around $60 million in highway funds for ferries. Much of the windfall will be spent in Maui County, enhancing Hawai‘i’s only existing interisland ferry services, which run from Lahaina to Lana‘i and Moloka‘i. (This project is unrelated to Hawai‘i Superferry, the private company discussed in Part I of this story.)

“Boating hasn’t been funded properly for the last decade,” says Ma‘alaea Harbor Agent Nicholas Giaconi. “Now we’re faced with some major renovations.” Giaconi oversees this tiny, busy harbor from his crow’s nest in the old SeaFlite building—a relic from the past that floods during big surf. Desperately needed improvements at Ma‘alaea will piggyback on the ferry project. Along with renovations extending interisland ferry service to Ma‘alaea, basic electrical and dock repairs and new wastewater treatment systems will bring the derelict harbor into compliance with the Environmental Protection Agency and the Americans with Disabilities Act.

At Lahaina Harbor, plans include a new dock to service ferries and cruise-ship tender boats, a second sewage pump-out, and new restrooms.

Rice calls the federal money “the best thing that’s happened to boating in 10 years.” He’s doing his best to maximize it, leveraging federal awards with smaller state appropriations. Still, design and permits for planned improvements will take three to seven years—not fast enough for a community that depends heavily on the water.

Public Outcry

The federal funds can’t keep Maui County’s entire boating program afloat. Giaconi says boaters compete for space at Ma‘alaea; he could easily fill twice his 200 slips. Commercial business invariably spills over to the under-developed boat ramps.

“There’s a lot of quarrels with local fishermen down at Khei boat ramp,” says recreational boater Clay Carvalho. “Maui Dive Shop uses it as a commercial spot, with buses unloading at 7 a.m. You’re supposed to stay for 15 minutes, but they stay a half hour.” Carvalho’s preferred boat ramp, Kahului, is under renovation. That leaves Ma‘alaea, which Carvalho says is too congested, Maliko, which is often too shallow, and Kihei, which Carvalho calls “humbug.”

Amanda Tillson, another boater, agrees. “It’s kind of a joke in the mornings because of all the snorkel boats. You can’t even drop your boat in the water.”

Once in the water, other problems arise. Few local destinations offer safe harbor for visiting vessels. Amanda’s husband, George Tillson, describes a recent trip to O‘ahu. “We sailed into Ala Wai at one a.m., not knowing the place had been condemned. It was awful.

There’s nothing safe for somebody desperate to tie up to there.” The majority of Hawai‘i’s boating facilities also lack fuel and sewage pumps. On Lana‘i, Tillson says, “we had to take our jerry jugs [gas tanks] by taxi into town

to refuel.”

Pumped Up

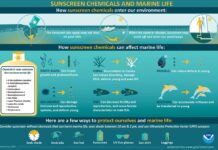

Last January, a local weekly publication ran a cover story with a photo of a toilet floating in the surf. Ever since, “Pump, Don’t Dump” activists have protested boat companies’ practice of emptying sewage tanks three miles offshore—currently legal. Most Saturday mornings, sign-wavers show up at Ma‘alaea to warn tourists what they might be swimming in.

Companies have few options. Ma‘alaea, like many harbors, doesn’t have a sewage pump-out system. For now, the only recourse is to hire a pump-out truck service. In many cases, pumping out requires retrofitting the vessel—something smaller companies may find prohibitively expensive.

Ecologically minded companies Trilogy and Pacific Whale Foundation (PWF) have led the way. PWF runs an “eco-truck,” which pumps out the company’s tanks, delivers biodiesel fuel, and transports recyclables. “It’s not just Ma‘alaea we’re concerned about; all boats need access to pump-outs,” says PWF spokesperson Ann Rillero. She testified before the State that the current situation is “simply unacceptable.” “Here we are on the world’s best island and these toilets are pretty close to third-world. We’re trying to be responsible for our own boats, but we’re also looking to address this problem in a broad state wide sense.”

While the State ponders, the County is responding. Mayor Alan Arakawa acted quickly to approve $30,000 to defray the costs of pump-out truck service. Maui County Council resolved to back temporary solutions until the permanent sewage system comes onboard.

Cruise Control

Meanwhile, Lahaina Harbor has a sewage pump-out that’s rarely used. Because of security measures put into effect after 9/11, the dock housing both the sewage and fuel pumps is inaccessible whenever cruise ships are anchored offshore.

This was among several concerns identified by the nonpartisan Cruise Ship Task Force appointed by Mayor Arakawa in 2003. Assessing the cruise industry’s increasing impact on Maui, the task force found that Lahaina Harbor is overwhelmed with cruise-related traffic. Cruise-ship tender boats continuously transport passengers to and from the ships. Minor collisions with other boats and docks occur frequently. Statewide, 12 accidents involving tender boats between 2004 and 2005 were serious enough to alert the Coast Guard; 10 occurred

in Lahaina.

Street parking is nonexistent when the flood of cruise-ship passengers arrives. Ferry passengers traveling to Lana‘i and Moloka‘i are inconvenienced, forced to wait outside of security areas. Even children attending nearby Princess Nahi‘ena‘ena School are affected; the fumes from idling tour buses waft into their classrooms.

The report also charted typical cruise-ship waste streams. Weekly air emissions can rival that of 10,000 cars. One million gallons of sewage, 110 gallons of photo chemicals, and unknown numbers of other hazardous wastes such as batteries can be dumped into the water each week. New state laws governing cruise-ship activities and emissions were passed last November, but critics complain that the laws are weaker than the Memorandum of Understanding they replaced.

Shifting Responsibility

With all these troubles threatening to burst the dam, it’s not surprising that the State has long contemplated unloading the responsibility of small-boat harbors, either to county or private management. DLNR Chairman Peter Young tested the waters, asking county mayors if they would consider assuming management of their boating programs. Only Mayor Arakawa responded positively; with two moneymaking harbors, Maui County has the best outlook. Big Island Mayor Harry Kim requested further discussion if the harbors were to be privatized.

Any talk of privatization stirs controversy. Some feel private managers are dramatically improving the situation. “Things are taken care of,” says Tillson, describing Ko ‘Olina, a privately-run harbor on O‘ahu. “You don’t have to go through red tape. You get showers and barbeques and the works, for about the same amount of money.”

But others fear that if handed to the private sector, the state’s smaller facilities would be abandoned.

“Nobody wants to take the low moneymakers,” says Giaconi. If harbors went to private management, he believes, “you’d see a change in clientele. The small fisherman would probably get muscled out.”

Carvalho says his family would be against privatization. “It’ll be about money. Fishermen are not rich. They just want to go out and enjoy the ocean.”

Rice says boaters need not worry. “Our harbors are not going to be put on the block and sold,” he says. “There’s never going to be a gate across any of our harbors.” He envisions contracting out individual management duties, while maintaining public access. “It’s common sense,” he says, “not a political issue. Private companies can be more responsive than the government in certain cases.”

Rice appreciates the public’s speaking up about boating. “I’d rather have them discussing it then ignoring it. When enough people talk about it, when it gets so bad, steps will have to be taken.”

This has already proven true on Maui. By stirring things up, the “Pump Don’t Dump” activists affected at least one harbor’s future. All the attention on Ma‘alaea caused engineers to change their plans for a single sewage pump-out to more boater-friendly pump-outs at each slip. While small, it’s a step in the right direction.