Jill Engledow | Illustrations by Guy Junker

The year is 2020, and green fields still flourish across Maui. Solar panels on thousands of roofs transform sunshine into hot water for thousands of families. Wind turbines spin electrical power from thin air. The sky over the Central Valley is clear. The vehicles on Maui’s roads emit few of the nasty pollutants produced by burning petroleum; some of them even trail a faint scent of French fries. The specters of fossil fuel depletion, political and geographic vulnerability have dimmed on an island that grows ever nearer to energy self-sufficiency.

The year is 2020, and green fields still flourish across Maui. Solar panels on thousands of roofs transform sunshine into hot water for thousands of families. Wind turbines spin electrical power from thin air. The sky over the Central Valley is clear. The vehicles on Maui’s roads emit few of the nasty pollutants produced by burning petroleum; some of them even trail a faint scent of French fries. The specters of fossil fuel depletion, political and geographic vulnerability have dimmed on an island that grows ever nearer to energy self-sufficiency.

Or, look at 2020 through a different lens. In this reality, electric bills and the cost of gasoline eat up a big chunk of every paycheck. Waste products of power plants and automobiles smudge the sky. No one knows when the next oil crisis will be, or how long the world’s supply will last. Hawai‘i, out here all alone in the Pacific, prays for tourists, and Mauians pray that tourists still want to visit an island whose dusty brown former sugar fields are being converted to subdivisions as fast as developers can pour concrete.

Which vision of tomorrow will become Maui’s reality? That depends in large part on efforts made today to find reliable sources of clean, renewable energy. Hawai‘i is already a leader in that area, producing about 7 percent of its energy from renewable resources, compared to a 2 percent national average. From geothermal energy in Puna, to garbage incinerated for “H-Power” on O‘ahu, to bagasse (sugarcane waste) burned at the HC&S mill in Pu‘unene, the state is off to a good start. Maui, with 6 percent of its energy from bagasse burning and another 9 percent from wind power, is ahead of the game.

Since 1996, Maui Electric Company has installed nearly 8,000 residential solar heaters. The pioneering Maui-based Pacific Biodiesel (see MNKO V. 8 No. 4) has perfected the art of turning used restaurant grease into automobile fuel (hence the french-fry smell in vehicles that burn its biodiesel). Kaheawa Wind Power’s towers are at work above Ukumehame (see MNKO V. 10 No. 2), and plans are underway for more wind power at ‘Ulupalakua.

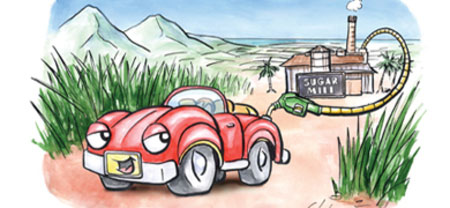

But wind power, while useful, is a “soft” energy source, available only when the wind blows. And neither bagasse nor wind can power an automobile. Ethanol can.

An alcohol derived from fermenting sugar-rich crops like corn or cane, ethanol is a “firm” energy source that can provide fuel for both transportation and electric plants. Ethanol already fills 10 percent of Hawai‘i’s gas tanks, and could someday provide much of Hawai‘i’s transportation fuel (as it does in Brazil), while lowering pollutants and greenhouse emissions.

At this point, all the ethanol in Hawai‘i is imported. Recognizing that both Federal and international trade laws prohibit the state from banning imported fuel, whether from the U.S. Mainland or other countries, the Legislature came up with a tax-credit plan to encourage the building of local ethanol processing plants. Two of the major players in the race to produce Hawaiian ethanol are old-time Maui farmers, Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company and Maui Land & Pineapple Company.

At this point, all the ethanol in Hawai‘i is imported. Recognizing that both Federal and international trade laws prohibit the state from banning imported fuel, whether from the U.S. Mainland or other countries, the Legislature came up with a tax-credit plan to encourage the building of local ethanol processing plants. Two of the major players in the race to produce Hawaiian ethanol are old-time Maui farmers, Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company and Maui Land & Pineapple Company.

Ethanol could be the saving grace for Maui’s sugar industry, which is searching for ways to survive in a volatile world market. If sugar fails, the green fields of Central Maui could turn into a weedy wasteland or be dotted with condos and mini-malls. The bagasse that has provided power for decades would disappear, along with any potential for ethanol production.

No one knows yet which crops make the best sense as feedstock for ethanol-processing plants. A new international consortium that includes Maui Land & Pineapple Company, Kamehameha Schools, and Kaua‘i’s Grove Farm Company is beginning research into that very question. ML&P CEO David Cole and major stockholder Steve Case are the connecting links in this partnership. Case also owns Grove Farm, and Cole sits on the Kamehameha Schools Board of Advisors.

One of Hawai‘i’s major landowners, Kamehameha already was researching the possibility of biofuel development, says Senior Vice President of Planning Mawae Morton. With 365,760 acres statewide, 95 percent in agriculture or conservation, “We’re committed to agriculture, and we’re committed to using agriculture to maintain green space in Hawai‘i,” Morton says. “If anything happened to either fuel supply or prices in Hawai‘i, that could have serious impacts” on the economy, to the detriment of both the schools and the native Hawaiian community that is Kamehameha Schools’ constituency. Joining forces with two other big landowners results in greater efficiency and less risk for the schools, Morton says.

The Hawai‘i BioEnergy consortium has just started to consider crops for ethanol production, say Morton and ML&P Vice President of Strategic Planning Brian Orlopp. With the three Hawai‘i partners in Hawai‘i BioEnergy holding hundreds of thousands of acres of agricultural land, “We hope there’s potential for more than one plant,” Morton says. “We know sugar well,” but it may not be the most efficient at producing energy. Something else may work better—perhaps sorghum, pineapple byproducts or certain grasses.

The consortium has to consider questions such as how much water a crop will need, whether it is safe to introduce a species into Hawai‘i’s invasive-sensitive environment, what to do with large amounts of waste products, and how to balance the continued need to grow food with the production of energy.

Hawai‘i BioEnergy has pulled in some heavy hitters to help answer these questions. The advisers (who also are investors) include Vinod Khosla, cofounder of Sun Microsystems and one of the world’s top venture capitalists, as well as a strong proponent of widespread adoption of ethanol in the United States. Also participating are two Brazilian companies, Brasil Bioenergia, formed by leading industrialist Ricardo Semler, and Tarpon Investments, an investment firm with expertise in Brazil’s energy sector.

Meanwhile, Pu‘unene-based Hawaiian Commercial & Sugar Company is studying the possibility of producing ethanol. HC&S is “still in our due diligence phase,” exploring various models for turning its sugar into a new product, says Lee Jakeway, HC&S director of energy development and planning. “If energy prices continue to go up, we have to be looking for alternatives.” And the sugar industry needs alternatives too: “The industry can’t remain the same. We can’t do business as usual.”

Jakeway says it’s not economically feasible now to convert raw sugar to ethanol production; sugar earns about $350 a ton. A more likely feedstock is molasses, a $75-a-ton byproduct of sugar production. If research into using plant waste such as the cane and leaves to make “cellulosic” ethanol is successful, “There’s one more economic incentive to recover the biomass,” Jakeway says. “That’s why the cellulosic ethanol is so attractive,” with its use of anything from cane waste to tree trimmings.

Cellulosic production might also mean an end to cane burning, now an integral part of the mill’s sugar processing, although, “We can’t say for a certainty we’re going to stop burning.” HC&S is watching the progress of cellulosic production carefully. “We’d rather see it work first before jumping into it,” Jakeway says.

The company is considering other combinations that might work financially, such as using some cane juice to make ethanol and some to make a locally refined, large-crystal “sugar in the raw” specialty product, rather than sending all cane juice to California for refining into white sugar.

There’s also the problem of what to do with a particularly pesky byproduct of ethanol called vinesse—which HC&S is looking at closely after Jakeway’s visit to Brazil earlier this year. Vinesse, left over after yeast digests the sugars in molasses into alcohol, is pretty stinky stuff. It also makes a good fertilizer, and in Brazil they simply spray it on the fields. In Hawai‘i, that stink will never pass public muster, so Hawai‘i ethanol producers will have to use much more sophisticated units than the simple distilleries the Brazilians use.

These issues are just part of the complex puzzle that must be pieced together if Hawai‘i is to produce ethanol from homegrown crops. All the different pieces of this potential industry have to move in tandem to make it work. For farmers to invest in crop development, they have to know there will be water for planting, uses for waste products, and ethanol plants to process their crops. Those who will build the plants want to know that, while they may have to import raw materials at first, eventually there will be locally grown feedstock and a steady market for the finished product.

But the issues are not insoluble, because ethanol technology has taken giant leaps in the last two years, say proponents, making it more efficient and profitable. “As much ethanol as we could make is a good thing here in Hawai‘i,” Orlopp says.

The state consumes about 400 million gallons of motor fuel a year, with Maui using around 78 million. If only 10 percent of that need is met by ethanol, Maui alone can use 7.8 million gallons of ethanol. Hawaiian Electric Company has committed to using 50 percent ethanol in a new plant it plans to build on O‘ahu, and even MECO’s plant could eventually run on ethanol, holding out the promise of a large, stable market.

Admittedly, ethanol production is only part of Hawai‘i’s reach for a “renewable portfolio standard.”

“A portfolio is not a single solution; it is a collection of solutions—a collection that, with luck, will be greater than the sum of its parts,” says Senator English. The Hana resident, who chairs the Senate Committee on Energy, Environment and International Affairs, says that no single project will meet the State’s official goal of producing 20 percent of Hawai‘i’s energy needs with in-state renewable resources by the year 2020. But by tapping a variety of underused resources, “We have the potential to generate jobs, revitalize our agricultural lands, and create indigenous energy,” says English.

Putting together the ethanol puzzle will be worth the effort, says Vinod Khosla. “There is something in it for everybody,” from lower fuel costs to cleaner air to fewer American dollars spent on foreign oil. Khosla believes that simple economics could make ethanol the fuel of choice for American motorists in as little as five years. While conversion to ethanol is not without problems, “on the whole, the trade-offs are overwhelmingly in favor of ethanol,” he says. “I don’t think of ethanol as an alternative fuel. I think gasoline should be the alternative.”