Story by Shannon Wianecki | Photography by Ryan Siphers

“This is a very ‘ohu day,” says Sam Gon III. We stand at the uppermost edge of Haleakala’s vast volcanic expanse, watching the morning mist tiptoe into Ko‘olau Gap. “‘Ohu is a warm, rising mist,” says Gon, with a grin. “It’s also me.” His middle name, ‘Ohukani‘ohi‘a, means “the mist that quenches the thirst of the ‘ohi‘a tree.”

He ties on a kihei (cape) and asks photographer Ryan Siphers and me to draw near. The three of us are about to embark on an overnight backpacking trip into Haleakala’s wilderness and before we do, it’s Hawaiian protocol to ask permission. Gon’s sonorous voice spills out across the fire-forged valley. Playing with the word ‘ohu, he announces who we are, where we come from, and what our intentions are. Gon possesses his Hawaiian ancestors’ knack for tucking kaona, or hidden meanings, into every syllable.

“Who are you asking permission from?” I ask. Gon pauses, then sweeps his arm across the vista. “All of the elements.” The lava boulders, the hesitant breeze, the storm petrels hidden in their burrows . . . according to Hawaiian cosmology, familial ties connect us to every aspect of nature. In addition, certain plants and phenomena are kinolau, embodiments of specific gods. Today we enter their place: wao akua, the uplands. Realm of the gods. It’s appropriate to introduce ourselves first.

“Who are you asking permission from?” I ask. Gon pauses, then sweeps his arm across the vista. “All of the elements.” The lava boulders, the hesitant breeze, the storm petrels hidden in their burrows . . . according to Hawaiian cosmology, familial ties connect us to every aspect of nature. In addition, certain plants and phenomena are kinolau, embodiments of specific gods. Today we enter their place: wao akua, the uplands. Realm of the gods. It’s appropriate to introduce ourselves first.

When I checked the weather forecast yesterday, it predicted rain, all weekend long. Gon, who flew over from O‘ahu for this trip, shrugged, unconcerned. During his four decades as a field biologist in Hawai‘i, he has explored the archipelago’s mountains in all of their moods. Still, he interprets the unexpected sunshine and the wind’s momentary stillness following his chant as benevolent signs.

Gon straddles two worlds: scientific and spiritual. For the past thirty years he’s worked for The Nature Conservancy, evolving from ecologist to director of landscape conservation. Since 1995, he’s practiced traditional Hawaiian chant, hula, and protocol — a student of revered kumu (teacher) John Keolamaka‘ainana Lake. Fortuitously, Gon’s worlds intersect. After he graduated as a kahuna kakalaleo (chant practitioner), his bosses at The Conservancy added this new skillset to his official duties. He sits on the state’s Board of Land and Natural Resources and works closely with the Hawaiian Lexicon Committee, helping steer the future of Hawai‘i’s landscape and its native language.

Gon straddles two worlds: scientific and spiritual. For the past thirty years he’s worked for The Nature Conservancy, evolving from ecologist to director of landscape conservation. Since 1995, he’s practiced traditional Hawaiian chant, hula, and protocol — a student of revered kumu (teacher) John Keolamaka‘ainana Lake. Fortuitously, Gon’s worlds intersect. After he graduated as a kahuna kakalaleo (chant practitioner), his bosses at The Conservancy added this new skillset to his official duties. He sits on the state’s Board of Land and Natural Resources and works closely with the Hawaiian Lexicon Committee, helping steer the future of Hawai‘i’s landscape and its native language.

Of all the places he’s reconnoitered, Haleakala National Park ranks among his favorites. He first volunteered here in the late seventies, while conducting his doctoral studies on Hawaiian happy faced spiders. “To do entomology in this place,” he says, “you have to spend a long time laying on the ground.” In between spider hunts, he helped build fences, monitor rare plants, and eradicate invasive species within the park.

This year, Haleakala celebrates its 100th birthday as a national park. President Woodrow Wilson established the National Park Service in 1916. Hawai‘i Volcanoes and Haleakala were among the first inductees; they started out as a single park and became two in 1960. For at least 1,000 years prior, Hawaiians have climbed the 10,023-foot summit. When they did, it was for specific purpose: to study the stars, perform sacred ceremonies, or gather resources. From inside the crater, they collected fine-grained basalt for making adzes, and fat ‘ua‘u (storm petrel) chicks, a delicacy reserved for chiefs. Though it’s hard to imagine, the crater also served as a shortcut between Central and East Maui. Tough Hawaiian feet would’ve had no trouble navigating the cinder trails, says Gon — who, in his five-toed Vibrams, is close to barefoot himself.

This year, Haleakala celebrates its 100th birthday as a national park. President Woodrow Wilson established the National Park Service in 1916. Hawai‘i Volcanoes and Haleakala were among the first inductees; they started out as a single park and became two in 1960. For at least 1,000 years prior, Hawaiians have climbed the 10,023-foot summit. When they did, it was for specific purpose: to study the stars, perform sacred ceremonies, or gather resources. From inside the crater, they collected fine-grained basalt for making adzes, and fat ‘ua‘u (storm petrel) chicks, a delicacy reserved for chiefs. Though it’s hard to imagine, the crater also served as a shortcut between Central and East Maui. Tough Hawaiian feet would’ve had no trouble navigating the cinder trails, says Gon — who, in his five-toed Vibrams, is close to barefoot himself.

The sun is already high as we tromp down the trail from the summit, weighed down by our packs. I’ve been visiting Haleakala since I was eleven, but this is Siphers’s first visit. He’s bowled over by the panorama. Red, black, and taupe cinders swoosh down the steep crater walls, each colored stripe a geologic clue. The trail’s name makes perfect sense: Keonehe‘ehe‘e, Sliding Sands. The terrain looks active, volatile, as if the eruption is still happening, but in slow motion.

The sun is already high as we tromp down the trail from the summit, weighed down by our packs. I’ve been visiting Haleakala since I was eleven, but this is Siphers’s first visit. He’s bowled over by the panorama. Red, black, and taupe cinders swoosh down the steep crater walls, each colored stripe a geologic clue. The trail’s name makes perfect sense: Keonehe‘ehe‘e, Sliding Sands. The terrain looks active, volatile, as if the eruption is still happening, but in slow motion.

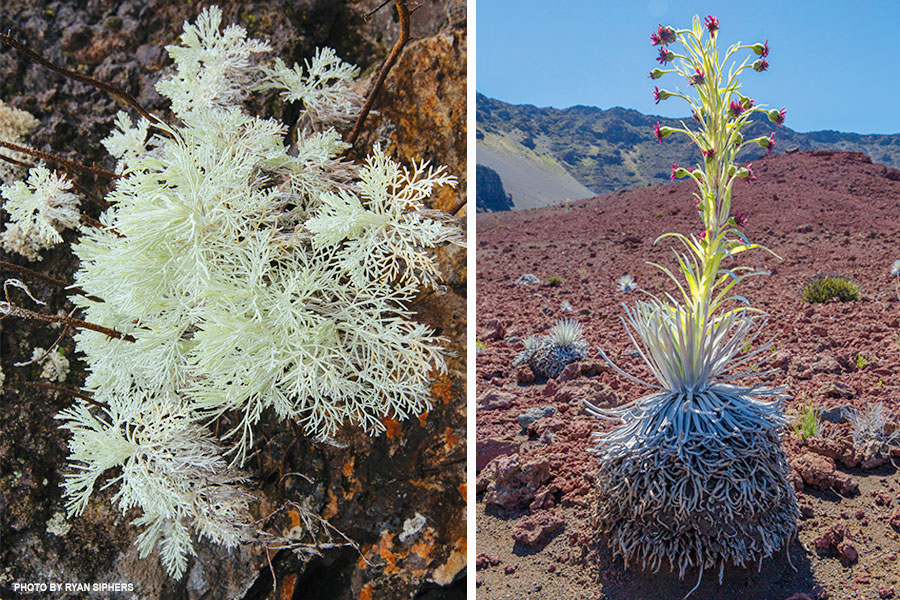

Gon points out each new plant species we encounter with fresh delight, as if spotting a friend. He particularly likes the fractal-like kupaoa a close relative of the famous Haleakala silversword. Gon and Siphers stop often to photograph favorite specimens. At this rate, our 7.4-mile hike to the Holua campground will take all day. Fine by me. The slow pace allows me time to prod Gon for stories. He starts with a tale of trickery:

“Hua, a chief from Hana, sent his bird catchers out for ‘ua‘u. There was a kapu [restriction] on the lowland nests, but the bird catchers didn’t want to hike all the way up to the Haleakala nests. Instead, they caught some lowland chicks and rubbed their bellies with cinder dirt. The chief’s kahuna [priest], Kaluaho‘omoe, saw through the deceit immediately and confiscated the ‘ua‘u. The bird catchers then told Hua that the priest had kept the birds for himself. So Hua had Kaluaho‘omoe burned alive in his hale [house]. Three years went by; no rainfall. A kahuna on O‘ahu saw that the devastating drought was spreading. He looked for clouds. The only clouds he found were above remote Hana‘ula in West Maui. He went there and found Kaluaho‘omoe’s two sons, who had fled before the fire. The kahuna asked for forgiveness and made offerings. The drought ended.

“Meanwhile, the folks that perpetrated the disaster were all dead. The proverb says, Nakeke na iwi o Hua i ka la, ‘the bones of Hua rattle in the sun.’ Because of the drought, when Hua died, there were no keepers to hide his bones. They were left exposed, which is the ultimate disgrace.”

“Meanwhile, the folks that perpetrated the disaster were all dead. The proverb says, Nakeke na iwi o Hua i ka la, ‘the bones of Hua rattle in the sun.’ Because of the drought, when Hua died, there were no keepers to hide his bones. They were left exposed, which is the ultimate disgrace.”

Heavy. I assume that the story’s message is: don’t lie and don’t trust liars. But Gon explains the ecological ramifications. “It’s a lesson about long-term consequences,” he says. “Every generation inherits issues from the generations before. Despite the fact that we are not responsible for creating it, we are responsible for fixing it.”

After Haleakala became a national park, considerable efforts went into restoring the native ecosystems. For many years prior, ranchers had run cattle through the crater. Feral goats ranged freely, nibbling rare native trees to nubs. It took park staff, volunteers, and local hunters the better part of a century to remove the animals and fence the park’s perimeter. Without their labors, many of Haleakala’s treasures would have been lost.

A single mamane tree stands beside a hitching post at the base of the trail. The only shade for miles, it welcomes every passerby: human, horse, bird, or insect. We sit beneath its low branches and share lunch.

A single mamane tree stands beside a hitching post at the base of the trail. The only shade for miles, it welcomes every passerby: human, horse, bird, or insect. We sit beneath its low branches and share lunch.

As we continue into the heart of the crater, each step further removes us from cellphone range, from the ceaseless hum of modern life. I feel deep gratitude for those who fought to keep helicopters out of this airspace. I think of John Muir, that tireless champion of untrammeled horizons. In Our National Parks, he wrote, “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity.” He wrote that 115 years ago.

Right now, in this wildness, the only sounds are the huff of my own breath and my boots sinking into the gravely sand. Occasionally a breeze ricochets through the pu‘u, or cinder cones. Haleakala has been called the quietest spot on Earth. In the stillness, time evaporates. It is a human contrivance, after all.

Right now, in this wildness, the only sounds are the huff of my own breath and my boots sinking into the gravely sand. Occasionally a breeze ricochets through the pu‘u, or cinder cones. Haleakala has been called the quietest spot on Earth. In the stillness, time evaporates. It is a human contrivance, after all.

This silent, scorched moonscape may appear devoid of life, but Haleakala shelters an assortment of extraordinary species that exist nowhere else. The silverswords speckling the side of Ka Moa o Pele, a large brick-red pu‘u, look like little metallic porcupines, some topped with flower bouffants. Sam is heartened to see so many keiki (young) plants. It’s a hopeful sign in an ecosystem already showing the ravages of climate change. The soft geometry of this spot reminds me of something Georgia O’Keeffe might paint. Three pu‘u of various hues — red, faun, and grey — overlay each other to form a deep V. Cloud shadows flicker across their faces. Fog seeps into the passage between like an inhalation.

We come to a crossroads between the two largest pu‘u. It has the potent energy of a fairy tale. I expect a troll or hobbit to appear. Instead, we see a mound of rocks, which Gon says could be a burial. “If you were pili [close] with your akua [god] you could be buried here.” The site’s remoteness guaranteed that your bones — and your mana, or spiritual power — wouldn’t be disturbed. For the same reason, Hawaiian mothers journeyed to the summit to hide their newborns’ umbilical cords.

We come to a crossroads between the two largest pu‘u. It has the potent energy of a fairy tale. I expect a troll or hobbit to appear. Instead, we see a mound of rocks, which Gon says could be a burial. “If you were pili [close] with your akua [god] you could be buried here.” The site’s remoteness guaranteed that your bones — and your mana, or spiritual power — wouldn’t be disturbed. For the same reason, Hawaiian mothers journeyed to the summit to hide their newborns’ umbilical cords.

We pass beyond the north ridge into Ko‘olau Gap’s cloudscape. The air itself is wet. This isn’t ‘ohu, it’s noe: a cold, descending cloud. I wonder what it must’ve been like to traverse this extreme terrain in the days before waterproof coats and feather-light packs. We’re crossing a flat, long-cooled lava plain, but beneath us, untamed forest tumbles down to Ke‘anae Peninsula, to the edge of the ocean.

A few years back Gon and some colleagues went looking for remnants of the King’s Highway in this remote region. They found evidence: a few polished rocks and C-shaped structures that offered protection against prevailing winds. They also found a rare endemic iris, mau‘u ho‘ula ili. Traditionally, Hawaiians used the plant’s juice to redden the ili (skin), making a temporary tattoo. Gon and company thought it would be fun to experiment. They cut the iris’s leaves into geometric patterns and taped them onto their arms, forehead, and ankles. A few hours later, hot red blisters formed. It turns out that the leaves should’ve been applied for just one hour, and that “temporary” meant a year or more!

A few years back Gon and some colleagues went looking for remnants of the King’s Highway in this remote region. They found evidence: a few polished rocks and C-shaped structures that offered protection against prevailing winds. They also found a rare endemic iris, mau‘u ho‘ula ili. Traditionally, Hawaiians used the plant’s juice to redden the ili (skin), making a temporary tattoo. Gon and company thought it would be fun to experiment. They cut the iris’s leaves into geometric patterns and taped them onto their arms, forehead, and ankles. A few hours later, hot red blisters formed. It turns out that the leaves should’ve been applied for just one hour, and that “temporary” meant a year or more!

By late afternoon, we reach the Holua campground, tucked up against the crater’s western wall. At 6,940 feet, it’s chilly and wet, but not mind-numbingly cold the way the summit can be. We pitch the tent and assemble our dinner: steamed breadfruit, smoked fish, baked sweet potato, and poi, sprinkled with black sea salt. It’s similar to what Hawaiians of the past might’ve eaten. Gon chants over our little feast — thrice blessed by the fisherman and farmers who contributed to it. Food shared in this manner is true sustenance.

The sun drops away, and stars pierce the velvet sky — one by one and then by hundreds. Dark clouds swiftly gather to blot it all out. Rain dumps hard all night, but we sleep snug and dry in our tent. In the morning, we are greeted by a full horseshoe rainbow shimmering in the mist next to our tent. Giddy as kids, we scamper across the lava flow, capturing photographic proof of this miracle and trying to stand beneath it.

We pack up and head out. Holua’s resident nene (Hawaiian geese) honk and hiss goodbye. Today’s hike is mostly uphill, up the Halemau‘u switchbacks that cut across a sheer, forested cliff face. We ascend through a drenching mist. I crush a sprig of endemic wormwood between my fingers. Its feathery, gray leaves are referenced in its name, hinahina (silver/gray) ku pali (standing tall on the cliff).

I ask Gon a question I’ve been pondering. How would a Hawaiian approach to conservation differ from the current Western model?

I ask Gon a question I’ve been pondering. How would a Hawaiian approach to conservation differ from the current Western model?

“It would involve more community,” he says, pausing to marveling over a spectacular scarlet fern. “The people who live in a region and know its resources intimately would be consulted. And rules wouldn’t be permanent, but contextual; they would change with seasons.” He offers the ‘ua‘u from yesterday’s story as an example: the kapu during their breeding season allowed populations to rebound. In the past, the konohiki — a kind of caretaker or true landlord — would observe the plants, animals, and weather over the course of a year or much longer. If things were imbalanced, action was taken.

Perhaps Haleakala could again be managed this way. Indigenous resource management has a modern precedent. In 2014, the New Zealand government ceded ownership and responsibility of Te Urewera National Park to a new board guided by traditional Maori principles. The law establishing the board acknowledges that “Te Urewera is ancient and enduring, a fortress of nature, alive with history; its scenery is abundant with mystery, adventure, and remote beauty.”

Soaked through with sweat and mist, we reach the top of the switchbacks. Gon pauses to look back and offer a chant of thanks. I recall the protocol at the start of our journey. More than eleven miles and twenty-four hours later, our orientation on this planet is different. New. Where we come from, who we are, and our intentions have shifted ever so slightly.

If You Go:

- To explore Haleakala’s backcountry, you need a permit, which you get after watching a short film at park headquarters. Tent camping is free with park entrance fee, but limited to three nights. If you prefer to stay in one of the three wilderness cabins, reservations can be made online. They cost $75, sleep up to 12, and book far in advance.

- Take two cars. Park one at Halemau‘u Trailhead (your endpoint) and the other at Keonehe‘ehe‘e Trailhead (your starting point).

- Weather conditions can be extreme, ranging from snow to intense solar radiation. Bring layered clothes, sunscreen and raingear.

- Leave no trace. If you packed it in, pack it out.

- Bring water and a water filter. Cabins have nonpotable water.

- Walking for hours on uneven lava and steep inclines can be strenuous. Wear sturdy shoes, and bring moleskin, first aid kit, and walking sticks.

- For more information, visit NPS.gov/hale.