Story by Teya Penniman | Illustrations by Matt Foster

Sweet papayas turn gold just outside the window of my north shore home. Kabocha squash hide among dark vines along the drive, while bursts of red chili peppers inflame the bush in the middle of our garden. Flattened stalks of last season’s turmeric and ginger tell tale of pungent roots below. But it’s the breadfruit tree I’m keeping my eye on.

Sweet papayas turn gold just outside the window of my north shore home. Kabocha squash hide among dark vines along the drive, while bursts of red chili peppers inflame the bush in the middle of our garden. Flattened stalks of last season’s turmeric and ginger tell tale of pungent roots below. But it’s the breadfruit tree I’m keeping my eye on.

Despite a mild climate and year-round growing season, Hawai‘i imports an estimated 90 percent of its food. Our geographic isolation in the middle of the Pacific leaves us vulnerable to shocks in our food distribution system. A natural disaster could destroy harbors or airports, while crop diseases or a distant political event could interrupt shipments, quickly depleting the Islands’ cupboards. No one knows for sure, but urban lore says that if the ships and planes stopped coming, our food supplies might last a few weeks. During peak visitor seasons, fresh lettuce, eggs, and meats would fly off the shelves even more quickly. A few banana bunches or liliko‘i ice cubes couldn’t breach a major gap.

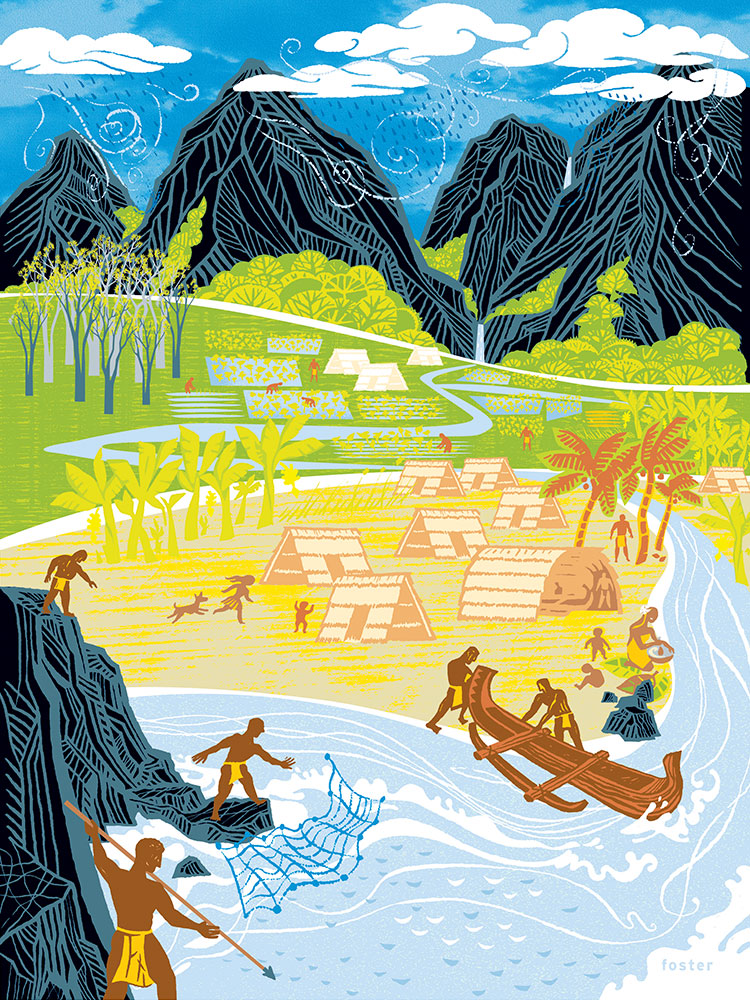

Hawai‘i is renowned for its efforts to reduce dependence on imported energy sources, but not so much for food security. Island history shows it doesn’t have to be this way. Before the Europeans arrived, a mauka-to-makai (mountain-to-sea) land-management system provided enough food for all, with the population estimated at close to today’s numbers. While ancient Hawaiians weren’t immune to droughts or other weather woes, the fertile lands, healthy streams and rich seas generally meant the masses weren’t a fortnight away from a major food fight.

The transition to an import-dependent food economy probably started with the Great Māhele—the redistribution of land by King Kamehameha III enacted in 1848—which eventually resulted in non-Hawaiians owning nearly one third of all private land. Private land ownership ushered in the plantation era, which further transformed traditional farming and fishing practices, as mono-crops dominated the landscape. With tourism, the Islands became more connected to the rest of the world; more frequent arrivals of planes and ships increased accessibility to food grown elsewhere, at lower prices. The lure of tropical living fueled subdivisions of agricultural land into two-acre “gentlemen’s estates,” helping to drive up local real-estate values and placing homes and farms out of reach for many residents.

Today, export crops account for nearly 80 percent of farmed land, with sugar, seed production, macadamia nuts, commercial forestry and coffee playing lead roles, crops not likely to satisfy a local food shortage. Previous government-funded efforts to help transition old plantations to diversified agriculture have been minimally successful. Farming in Hawai‘i presents unique challenges, especially to aspiring farmers. What are the key impediments to growing our own, and what we doing about it?

“The cost of land is astronomical,” says Dale Bonar, former executive director of the Hawai‘i Island Land Trust, who’s become involved in food-sustainability issues. Absent the ability to own land, farmers can only lease, making them reluctant to invest in needed infrastructure. “If you lose the lease, you lose your equity,” he says. Maui County’s 445-acre Kula Agricultural Park supports twenty-six farmers, offering long-term tenure with reasonable rent, but more affordable land is needed, and Bonar is adamant about the importance of having on-site housing. “You need to have eyes on the land,” he says, to protect against theft, vandalism, crop-munching deer and other pests. Bonar’s brainchild? The Affordable Farming Land Trust Maui. He explains that landowners could make tax-deductible donations of land or easements to the trust, which would provide long-term leases to farmers. Investments the farmer makes in the land, such as farm dwellings or irrigation improvements, could be passed on to the kids or sold at affordable levels to new farmers. The concept has garnered support from a broad range of agricultural leaders on Maui, but has yet to clear legal hurdles at the county level.

Existing government policies, such as reduced property taxes and lower water rates for agricultural use, are designed to support the industry, but farmers aren’t feeling the love. The Maui County Council has been trying to change tax rates to weed out faux farms, but one proposed system could have pushed legitimate operations out of business, says Maui County Agricultural Specialist Kenneth Yamamura. Especially problematic were provisions that required owners to dedicate their land to farming for the next twenty years to avoid paying thousands more in taxes. An older farmer would have to choose between a shorter term of dedication and higher taxes, or selling off. Yamamura says that some properties have dozens of heirs; trying to get seventy people to commit the land to decades of farming would have meant the demise of agriculture for that parcel. After dozens of meetings and hours of impassioned testimony, the bill returned to the drawing table, but left lingering questions about how to prune the system without killing the tree.

At the state level, acreage designated by each county as “Important Agricultural Lands” can qualify for valuable tax credits or loan guaranties, thanks to a 1978 initiative designed to preserve large, contiguous blocks of agricultural land. But according to Maui Planning Director Will Spence, State funding to determine which lands qualify has never materialized. Spence lauds the affordable-farming concept proposed by Bonar, adding that the ability to cluster houses or other infrastructure would create larger contiguous pieces for farming. His department is seeking to expedite farming applications, which currently require navigating three different departments—a daunting process for those who want to add revenue with farm tours or farm-to-table dinners.

The announcement in late 2015 that the state’s last sugar plantation was shutting down added a giant question mark to Maui’s landscape. While some envision repurposing both the water and land for more diversified operations (albeit in the absence of a clear nod in that direction from landowner Alexander & Baldwin), others predict economic hits to smaller farms that will no longer be able to piggyback on large-scale purchases and shipments from the mainland. At a minimum, the county will lose some 650 jobs in agriculture. Simon Russell, vice chair for the Hawai‘i Farmers Union United (HFUU) and a member of the Hawai‘i Board of Agriculture, says, “We need to have a well-thought-out, polite conversation” to prevent transforming 36,000 acres of Central Maui into a desert.

Meanwhile, the backs aren’t getting any younger: on average, farmers in the state are sixty years old. But there are bright spots. Efforts to grow more farmers, expand local expertise and develop new marketing options seem to be taking root with an abundance of partnerships and programs. The HFUU has a Farm Apprentice Mentoring program that has paired young farmers with experienced elders who share their mana‘o (knowledge) and commitment.

The Maui County Farm Bureau’s Agriculture in the Classroom project combines field trips, school visits and career-opportunity days to raise awareness about where the corn, kale and burgers on our plates come from. The Bureau also hosts the annual Maui County Agricultural Festival, highlighting the role of agriculture in the community, providing a venue for small-scale growers, and linking farmers and top chefs in cooking demonstrations. Statewide, the new legislatively created Farm-to-School project advocates buying food locally for public schools to help leverage taxpayers’ dollars in support of food self-sufficiency; the program coordinator lives on Maui.

The local nonprofit Grow Some Good has been hugely successful: forty-two school gardens across Maui County’s three populated islands are getting keiki hands in the soil, lo‘i (taro paddies) and compost, while helping them discover the joys of harvesting their own veggies or capturing honey from beehives. Many of the schools integrate lessons from the gardens into the curriculum.

For the backyard gardener and commercial producers alike, the Sustainable Living Institute of Maui at UH–Maui College offers a variety of workshops, from composting, to building a shed, to arborist certification. The college’s new Food Innovation Center provides training in food safety, manufacturing practices and marketing. The center also has a certified commercial test kitchen.

On the east end of the island, Hāna Ranch has embraced the challenge of self-sufficiency, pledging to “produce for Maui first,” according to Operations Manager Brian McGinness, who says, “Growing calves and selling them to the mainland doesn’t contribute to food security.” The ranch’s “stacked enterprise” approach includes developing new markets to sell its products; its Pā‘ia restaurant, Hāna Ranch Provisions, features Hāna-grown produce and ‘ono (delicious) beef. McGinnis says they are an experiment in progress; focusing on what grows well here will require fewer inputs like water, fertilizer or pest control.

Besides complying with the annual hurricane-season advice to stock up on batteries, canned fish and rice, what can the rest of us do to simultaneously help avoid and prepare for a run on local food supplies? Maybe start with that breadfruit tree.

Breadfruit, or ‘ulu in Hawaiian, is a canoe plant—carried with the Polynesians wherever they journeyed across the Pacific. The fruit is packed full of calories and nutrients; a single tree can drop 450 pounds each season, and it grows to a majestic, productive tree in fewer than ten years. You just need to learn how to cook it; to the uninitiated, ‘ulu tastes quite bland. Maui has the most extensive collection of breadfruit species and varieties in the world. The folks at the National Tropical Botanical Garden in Hāna are happy to share their knowledge and recipes with you.

As happens in Hawai‘i, sometimes a passerby or neighbor asks to harvest from the bounty of our yard. Over the years we’ve happily shared our fat round ‘ulu. But if those ships stop coming. . . .

Got an appetite to learn more?

While you’re waiting for your ‘ulu tree to start dropping fruit, check these resources:

- Affordable Farms Maui ~ AffordableFarmsMaui.org

- Agricultural Land Use Baseline Study ~ Hdoa.Hawaii.gov/salub

- Grow Some Good ~ GrowSomeGood.org

- Hāna Ranch ~ HanaRanch.com

- Hawai‘i Farmers Union United ~ HfuuHi.org

- Maui County Farm Bureau ~ MauiCountyFarmbureau.org

- National Tropical Botanical Garden ~ Ntbg.org/gardens/kahanu.php

- Sustainable Living Institute of Maui ~ SustainableMaui.org

How prepared are you?

- Do you have a garden with year-round fruits and vegetables, including leafy greens, citrus, papaya or bananas, avocado, taro or breadfruit—and know how to cook them?

- If your garden produces more than you consume, do you have a sharing network?

- If you can’t have a garden, do you own shares in a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) network? (You can share the risks and benefits of supporting a local farmer.)

- Do you patronize farmers’ markets, verifying that the products offered are locally grown?

- Do you choose local food first, both in your purchases and by asking vendors and restaurants whether they buy local?

- Do you educate yourself about political and policy issues important to local producers?

- Do you support one or more of the organizations mentioned in this story?

- Have you thanked a farmer or rancher recently? No farmer, no food!

How many “yes” answers did you have?

7–8 You and your ‘ohana (family) should be fine. You might want to invest in a locked pantry.

4–6 You probably won’t starve, but you might consider taking up fishing.

1–3 You could be knee-deep in compost if the ships stop coming. Find a community garden or CSA network to increase your food-security score!

By the Numbers

Since 1970, the state’s dairy industry dropped from 120 operations to a lonely 2 on the Big Island, and Hawai‘i’s ranches now provide just 6 percent of meat consumed locally, down from 30 percent.

Since 1980, total acres farmed diminished 57 percent. By the end of 2016, the state’s last sugar plantation will shut down; the fate of those 36,000 acres on Maui is unknown.

Ranchers have seen a 31 percent decrease in pasturelands since 1980; some lie fallow or now grow houses.

Cropland statistics are from the Statewide Agricultural Land Use Baseline 2015, prepared by Jeffrey Melrose, Ryan Perroy and Sylvana Cares at UH–Hilo for the Hawai‘i Department of Agriculture.